The conversation around housing in Addis Ababa is never just about economics. It is a deeply emotional, social, and personal discourse that strikes at the very heart of security, legacy, and belonging. My previous article, which framed the city’s property dream as a “peculiar kind of fever,” aimed to dissect one specific aspect of this complex issue: the stark financial irrationality of the negative-carry mortgage. It argued that paying a small fortune each month to own a house you could rent

The response was thoughtful and engaging, proving that this is a subject that matters deeply to many. One reader’s comment, in particular, offered a crucial refinement. He found the financial critique persuasive but rightly pointed out that the solution cannot be singular. He argued that the drive for ownership is tethered to profound social realities—tenure security, marital power, and intergenerational asset transfer—that no analysis can ignore. He called for a broader conversation, one that includes housing-side measures, financial liberalization, and the development of democratized institutions like transparent price registers and reliable realtors.

This perspective is not just valid; it is essential. It provides the perfect opportunity to build a bridge, to clarify that the original argument was never a dismissal of the human yearning for a home, but a targeted critique of the broken financial pathway that so many are forced to walk. The objective is to advocate for a system where the dream of ownership is a wise and sustainable choice, not a desperate and financially draining compulsion.

We must begin by honoring the soul of the matter. To reduce the quest for a house in Addis Ababa to a simple spreadsheet calculation is to miss the entire point. A house is far more than an asset. It is a fortress of tenure security in a rental market that can feel precarious and unpredictable. It is the ultimate form of stability, a guarantee that a family will not be displaced by a landlord’s whim or a sudden rent hike. For many, having one’s name on a title deed is a profound source of power and agency within a household and society at large. It is tangible, undeniable proof of ownership and belonging. And perhaps most importantly, it is a bridge to the future – the most concrete way to leave a legacy for one’s children, an asset that can shelter, educate, and empower the next generation.

These motivations are not irrational. They are deeply human and fundamentally rational in a context where formal social and economic safety nets can be fragile. The original article was never intended to dismiss these powerful drivers. The intention was to ask a painful but necessary question: is the primary financial instrument used to achieve this security actually securing it, or is it secretly jeopardizing it?

This is where we find the trap in the path. The critique is not of the destination, but of the treacherous journey so many are forced to take. Consider a family committing to a two-decade loan with a monthly payment that dwarfs the average income, all for a house they could rent for a mere fraction of that cost. The difference in those monthly payments is not just a line item in a budget. It represents the cost of a child’s education, a robust family health emergency fund, or the seed capital for a small business. It is the very liquidity and resilience that the family seeks to build through ownership in the first place.

By shackling themselves to a debt that cripples their monthly cash flow, they become profoundly vulnerable. A job loss, a medical crisis, or an economic downturn could see them lose the very asset they are sacrificing everything to attain. The negative-carry mortgage, in this light, does not function as a tool for building security. It rather resembles a high-wire act that risks everything. It forces families into a state of being “house-rich” but “cash-poor,” systematically undermining their ability to save, invest in their children’s future, and weather life’s inevitable storms. Therefore, to frame this specific financial behavior as “irrational” is not a judgment on their aspirations, but an alarm bell about a system that makes the pursuit of those aspirations financially self-defeating.

So, what would a truly wise housing investment look like? It would be one that actually fulfills the promises of security and legacy without bankrupting the present. It would be affordable, meaning the monthly cost of ownership does not consume a family’s entire disposable income but coexists with the ability to live a full life, educate their children, and build savings. It would be rational, meaning the purchase price and financing terms bear a logical relationship to the property’s inherent value and potential for rental income, not just speculative hope. And crucially, it would be supported, which is where the reader’s incisive points on institutional reform come to the fore. A wise investment is made in a transparent market. This requires the very institutions he mentioned: public price registers to combat information asymmetry, reliable and regulated realtors to guide buyers fairly, and a competitive financial sector that offers better, more creative products than the current one-size-fits-all debt trap.

This brings us to the ultimate synthesis: the need to build an entire ecosystem of choice. The original call for deeper capital markets and a clearer understanding of opportunity cost was never intended to be a “single cure” to be swapped for another. It was a call to create viable alternatives. The fundamental pathology of the current market is that real estate has become the only perceived game in town for storing wealth and achieving long-term security. This stark lack of choice creates a desperate, compulsive demand that fuels speculative bubbles and makes basic housing unaffordable for those who simply want a place to call home.

Imagine where young professionals could confidently invest their monthly savings into a diversified portfolio of stocks, government bonds, or mutual funds. Suddenly, the immense pressure on a single family to pour every last Birr into a single, illiquid, hyper-expensive property would begin to ease. They could build a retirement fund and save for a home concurrently. They could achieve tenure security through a diversified and resilient asset base, not solely through a title deed purchased with crippling debt. This perspective champions a multi-pronged approach. On the demand side, we urgently need the housing-side measures and institutional reforms that make the act of buying a house safer, more transparent, and more sensible. On the supply side, we need the finance-side liberalization that creates a vibrant ecosystem of alternative investments, making the decision to buy a house a conscious choice among many good options, rather than a desperate compulsion born from a lack of alternatives.

When people have other credible places to grow their wealth, the speculative fever that currently grips the housing market can naturally cool. This, in turn, makes housing more affordable for those who truly want it as a home, not just as a speculative token. It breaks the vicious cycle where the house is both the problem and the only perceived solution.

The dream of a home in Addis Ababa is a noble one. It should be a source of pride and stability, not panic and perpetual debt. It should be a foundation for a better life, not an anchor dragging a family into financial distress. The original article was a diagnosis of the fever; this is a vision for a lasting recovery. It is a call to move from a system of compulsive, high-stakes betting to one of conscious, rational choice. By working simultaneously to reform the housing market and to build a broader, more robust financial ecosystem, we can create a future where investing in a home can finally be the wise, secure, and legacy-building decision that people have always intended it to be. Let us work towards building not just houses, but a system where those houses can truly become homes.

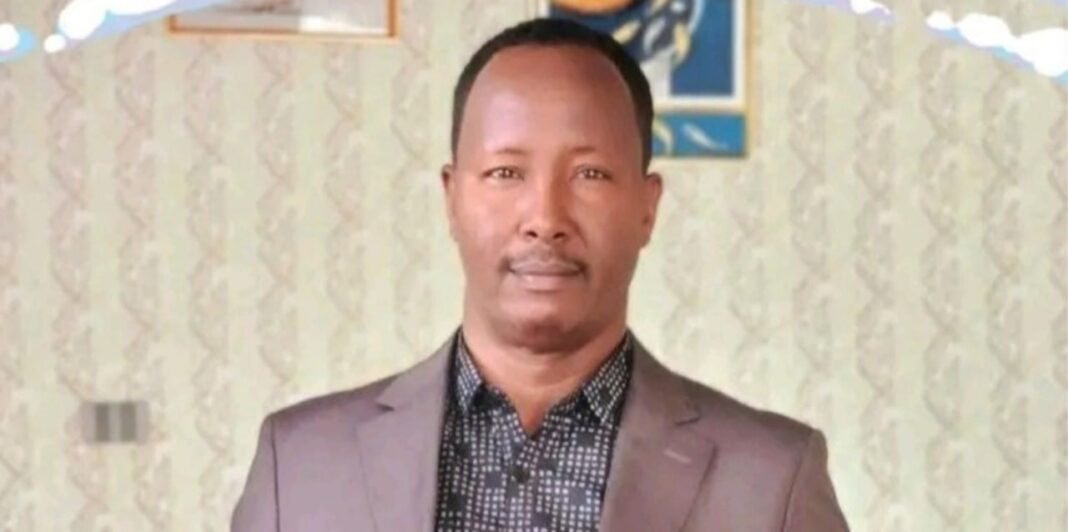

Befikadu Eba is Founder and Managing Director of Erudite Africa Investments, a former Banker with strong interests in Economics, Private Sector Development, Public Finance and Financial Inclusion. He is reachable at befikadu.eba@eruditeafrica.com.