Diplomatic staff in Tel Aviv and members of Israel’s Knesset have voiced concerns about the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) and its perceived lack of commitment to addressing the longstanding issues surrounding the Deir es-Sultan Monastery in Jerusalem.

The EOTC oversees several religious sites in the Holy Land, including locations in Jerusalem and surrounding areas under both Israeli and Palestinian administration, many of which are situated in areas of significant religious importance.

However, Deir es-Sultan is particularly noteworthy due to its historical significance. Ethiopia claims ownership of this site in the Old City of Jerusalem, a claim that dates back nearly three millennia to the time of King Solomon.

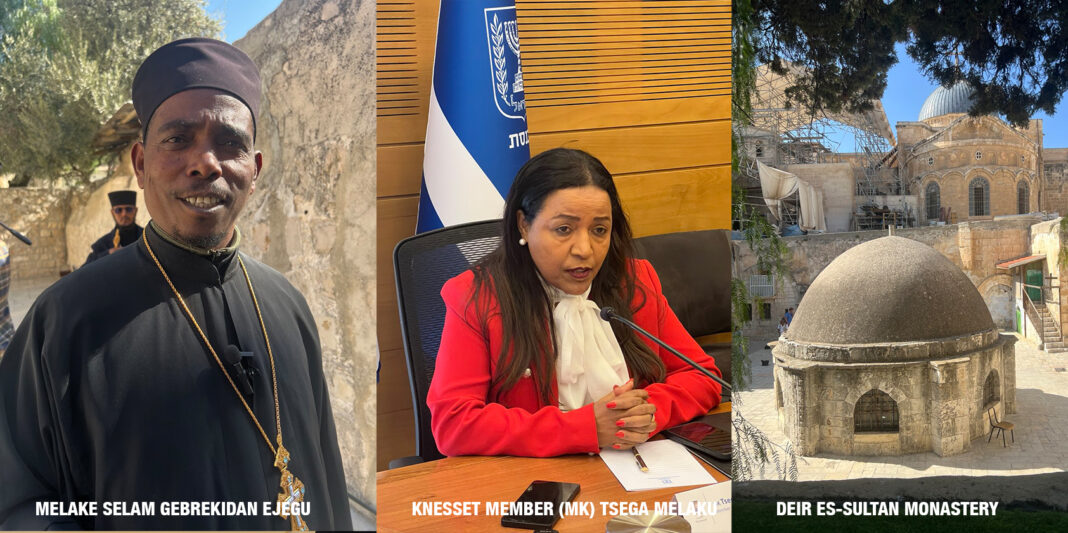

Monks, monastery leaders, and local tour guides emphasize that the monastery—perched atop the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Golgotha, the site of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion and near his resurrection—serves as a major destination for pilgrims and tourists.

Scholars highlight that the Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem has faced challenges in the modern era, especially during the “Era of the Princes,” a century characterized by decentralized rule that lasted until Emperor Tewodros II unified power in 1855.

During this period, Ethiopian monks and nuns encountered repeated attempts by Egyptian Copts to gain control of the site, which Ethiopia asserts has been under its stewardship since the time of the biblical Queen of Sheba.

Ethiopia maintains that the location served as the encampment for Makida, the Queen of Sheba’s retinue, during her visit to King Solomon.

It was later recognized as an Ethiopian site and eventually transformed into a monastery of what became the state church—the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

Ethiopian Ambassador to Israel Tesfaye Yetayew explained that despite historical evidence supporting Ethiopia’s claim to the site for 3,000 years, the dispute remains unresolved. He noted that the conflict escalated in the modern era, particularly as Ethiopia’s central government weakened due to internal power struggles.

While the EOTC manages around seven monasteries and churches in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and near Jericho’s River Jordan, the contested monastery at Golgotha remains the most sensitive issue.

Tesfaye pointed out that Israel enforces a law known as the “Status Quo,” established during the Ottoman period, which regulates relations among religious communities at holy sites.

“Although the monastery is administered by the EOTC, there are competing interests, and the Israeli administration prefers to maintain the Ottoman-era status quo,” he stated. The Ottoman Empire was the last long-standing governing authority in the region before the British Mandate took control after World War I.

“Currently, Ethiopia holds services at two churches within the complex—Holy Saviour and St. Michael—but undertaking renovations or obtaining basic municipal services like water and electricity is challenging under the Status Quo. Ethiopia does not possess a formal title deed due to this arrangement,” Tesfaye told journalists in Tel Aviv.

He noted a recent improvement: a house that was damaged by a fallen tree has been repaired. “During his visit to Israel in March, Foreign Minister Gedion Timotheos visited the monastery and spoke with the monks, who described their harsh living conditions. Our Foreign Minister raised the issue with his Israeli counterpart, Gideon Sa’ar, which led to the repair,” the Ambassador added.

“This case has persisted for nearly three centuries, but we remain hopeful for gradual progress,” he added.

He also highlighted the vibrancy and impressiveness of Ethiopian religious ceremonies and holiday events in Jerusalem, which should prompt authorities to offer better support to the monks. However, he expressed disappointment that the leadership of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) is not pursuing the matter with sufficient urgency.

A recent opportunity arose when Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar visited Addis Ababa. “The Israeli Foreign Minister met with the EOTC Synod, but the church leadership did not raise the issue,” Tesfaye stated.

Nonetheless, he assured that the Ethiopian diplomatic mission is actively working to safeguard Ethiopia’s interests regarding the monastery.

Knesset Member Tsega Melaku emphasized that Ethiopia is the only Sub-Saharan African country with religious property in Israel. “We have done our utmost to support the Ethiopian church in its dispute with the Egyptian Copts over Deir es-Sultan,” she said.

“I remember working with former MK Shlomo Molla to improve the lives of the monks, but they have faced challenges as well,” Tsega, who emigrated from Ethiopia to Israel at age 16, remarked during a press conference with Ethiopian journalists in Jerusalem last month.

“We persuaded the relevant Israeli authorities to assist the Ethiopian monastery, but progress has been slow, partly due to the frequent changes in monastery leadership and the fact that some leaders are abroad for months at a time. We were—and remain—eager to support them,” she explained.

Melake Selam Gebrekidan Ejegu, treasurer of Deir es-Sultan Monastery, told Capital that the prolonged conflict has left the church feeling frustrated.

“From the Patriarch down, the EOTC leadership has repeatedly engaged with the Israeli government, but there has been no improvement for 240 years. It is now clear that this issue cannot be resolved by the Synod alone; it requires direct government-to-government intervention,” he stated.

“When problems arise, the Synod does not seek to involve the Israeli administration directly. Instead, they prefer the Ethiopian government to take the lead in discussions,” Melake Selam added.

Currently, more than twenty monks and nuns reside at the monastery.

“Our urgent request is for the Ethiopian government to negotiate with Israeli authorities to renovate the monastery, which is in a serious state of disrepair,” he appealed.

MK Pnina Tameno, who shares Ethiopian-Jewish heritage with Tsega, emphasized the deep historical ties between Ethiopia and Israel, which should continue to strengthen socially, culturally, and politically.

“We are working on this, and we must continue to do so,” she stated during a press conference at the Knesset on November 19, referring to the Israeli government and lawmakers’ role in fostering bilateral relations.

The Ethiopian Deir es-Sultan Monastery is particularly appealing to tourists interested in early Christian history, Ethiopian Orthodox tradition, and unique cultural heritage sites.

It represents a centuries-old African presence atop one of Christianity’s holiest sites—the Church of the Holy Sepulchre—and embodies Ethiopian historical claims, legends of Solomon and Sheba, and a distinct rooftop community deeply connected to the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. Its story provides a unique narrative that is often overlooked by mainstream tourism.

The “Status Quo” regulation, formalized by Ottoman authorities in 1863 concerning Deir es-Sultan, stipulates that no physical or administrative changes may be made to the site without government approval. It was intended to prevent recurring disputes, particularly between the Coptic and Ethiopian Orthodox churches, over possession and rights.