A new soil “medicine” is helping farmers in Bule district and beyond defeat crippling soil acidity, boosting yields from a few quintals to harvests that can finally feed families and fuel Ethiopia’s growth.

Tesfaye Malei was once a man who had lost hope. A farmer in Bule district of the Gedeo Zone, he would rise before dawn to work a one‑hectare plot, only to harvest less than two quintals—about 200 kilograms—of grain. “All that labor for two quintals!” he recalls, his voice still marked by the frustration of those years. His soil, eaten away by acidity, made his effort almost meaningless.

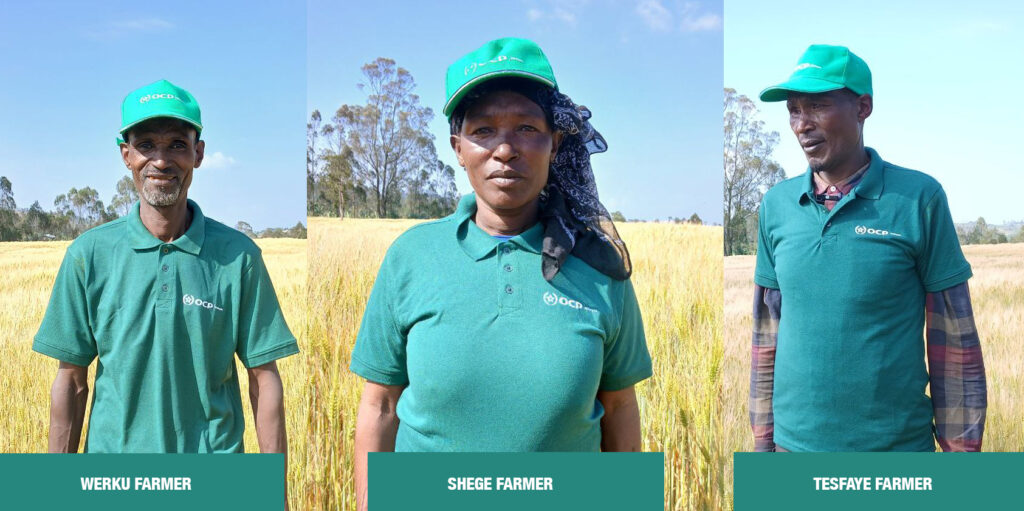

Today, Tesfaye stands in the middle of the same field and tells a very different story. “This land that used to give only two quintals per hectare now produces 50 or 60,” he says, smiling broadly as he looks over thick stands of barley. For him, this is not just a better harvest; it is a return of dignity and security—a resurrection powered by a new fertilizer technology called OC‑MASSA.

This is more than the story of one farmer. It is the story of a wider awakening in Bule, where farmers have begun to “bury” soil acidity and move into a new phase of prosperity. Their journey shows what can happen when science, policy reform, and farmers’ own determination finally pull in the same direction.

A Paradise with a Silent Killer

Located in Southern Ethiopia’s Gedeo Zone, Bule district looks like a green paradise from a distance. Sitting at an altitude of around 2,810 meters above sea level, it enjoys a cool highland climate and receives roughly 1,400 millimeters of rainfall per year—conditions that, on paper, seem ideal for barley, wheat, maize, and other highland crops.

Yet behind this apparent abundance lurked a silent killer: soil acidity. For years, farmers sowed seeds, applied fertilizers, and labored from dawn to dusk, only to harvest yields that were nowhere near commensurate with their effort. Many describe a sense of shame and helplessness as their land failed them season after season.

Research has since confirmed the scale of the problem. Nationwide, more than 40 percent of actively cultivated land is now considered acidic, with some regions—such as parts of Sidama, Southwest and South Ethiopia—reporting acidity on well over 60 percent of farmland. In total, around seven million hectares of Ethiopia’s arable land are affected by acidification, with about 3.2 million hectares severely damaged. In Bule district alone, 3,813 hectares are claimed by this “silent killer.”

Farmers Find a New Ally

For years, the main solution promoted to combat soil acidity was lime. Scientifically, lime works: it raises pH and helps unlock nutrients for plants. But practically, it has been a heavy burden on smallholder farmers. Correcting soil acidity using conventional lime can require 20 to 30 quintals per hectare, meaning huge transport and labor costs in rugged highland terrain.

“Transporting lime to solve soil acidity requires a lot of money and effort,” explains Dr. Selamyihun Kidanu, Director of Agronomy and Business Development at OCP Ethiopia. “For many farmers, moving up to 30 quintals of lime per hectare on steep, fragmented plots is simply not realistic. That is why OC‑MASSA was developed—to solve this bottleneck.”

OC‑MASSA is a customized fertilizer that combines phosphorus with calcium and granulated limestone in a single granular product. The idea is simple but powerful: instead of hauling many bags of bulk lime plus separate fertilizer, farmers apply a much smaller quantity of one product that both neutralizes acidity in the root zone and supplies missing nutrients—especially phosphorus, which is a key limiting factor in many Ethiopian soils.

The logistical advantage is striking. To treat acidic soil, OC‑MASSA requires only about three quintals per hectare—roughly one‑tenth of the lime requirement for similar effect. That alone can cut transport burdens and associated costs dramatically, especially in remote and hilly districts like Bule.

Worku’s Barley and the Power of Practice Change

When you meet Worku Kurse in his barley field, the brightness on his face rivals the lush green of his crop. Worku supports nine family members. For him, farming is not a side activity; it is the source of his children’s schoolbooks, the fund for a new roof, and the guarantee of daily bread.

“It used to be a big victory if we managed to get six quintals from one hectare,” he recalls of the days before OC‑MASSA. “We sowed in the old way, scattering seed by hand, and we just accepted whatever came.” That changed when extension workers and OCP agronomists introduced a package of practices: treating acidic soils with lime and OC‑MASSA, sowing in rows instead of broadcasting, and applying the right fertilizer at the right time.

“Now we start preparing our fields in May,” Worku explains. “We first treat the soil acidity and then sow in line. When we added OC‑MASSA, the result shocked us.” On land that once produced six quintals per hectare, Worku is now expecting around 30 quintals, enough to comfortably support his family of ten and invest back into his farm.

Farmers like Worku emphasize that OC‑MASSA alone is not a magic wand; it works best when combined with improved agronomic practices. But they are equally clear that without a practical way to tackle acidity, no amount of seed or technique could unlock their land’s potential. For them, OC‑MASSA is the missing piece that makes other improvements truly pay off.

Tesfaye’s Journey from Despair to Confidence

Few stories illustrate the emotional arc of this transformation better than Tesfaye’s. A few years ago, his yields had fallen so low that he considered abandoning farming altogether. “In the past, we used to get only two quintals from a hectare,” he recalls. “Imagine! Working an entire season for such a small harvest—it breaks your spirit.”

Everything changed when he joined demonstration plots managed with OCP Ethiopia and local experts. Over two seasons of applying OC‑MASSA and following improved practices, his fields were transformed. “Now the result is between 50 and 60 quintals,” he says, still sounding almost incredulous. “My hope has returned. I have decided to stay in agriculture. This new technology has given me confidence.”

Tesfaye’s experience is echoed by other farmers in cluster groups across Bule. Shege Shifera, who works with more than 20 farmers on a 10‑hectare barley block, points to the thick, uniform crop covering the hills. “This barley is not just sprouted; it is fed and grown with OC‑MASSA,” he says. “We have seen the benefits with our own eyes. From now on, even if there is no support, we will buy and use it ourselves.”

Science, Standards, and Policy Reform

Behind the visible “miracle” in farmers’ fields lies years of research, trials, and policy shifts. OCP Ethiopia and its partners spent around six years in laboratories and on experimental plots, collecting data across multiple regions and crops. By some estimates, OC‑MASSA delivers yield advantages of 20–30 percent over conventional blends on average, and up to 50 percent in particularly sensitive acidic zones.

Dr. Wondale Habtamu, Deputy Director General of the Ethiopian Agriculture Authority, underlines that OC‑MASSA is the product of a deliberate move toward science‑driven, private‑sector‑enabled agriculture. For decades, Ethiopia’s fertilizer system was tightly controlled by the state, with limited room for customized products or private investment. Now, that is changing.

“In the past, agriculture was constrained not only by law but by the way the sector was controlled,” he notes. “Today, we are opening space for private investors and encouraging innovation, but without compromising on quality and safety.” According to him, OC‑MASSA went through rigorous testing and meets standards set by the Ethiopian Standards Institute before being approved for wider use.

Wondale describes OC‑MASSA as more than a simple fertilizer—he calls it a “soil medicine.” Unlike standard products like urea or DAP, which mainly address nutrient deficiencies, this blend targets the underlying pH problem while delivering key nutrients. Farmers who used to haul 30 quintals of lime and other inputs per hectare can now achieve better results with around 3 quintals of this balanced fertilizer, reducing cost and labor while improving profitability.

A Broader Transformation Takes Shape

For local leaders, the change is visible in both fields and attitudes. Barako Beriso, Chief Administrator of Bule woreda, notes that while the district’s land is naturally fertile, acidity long blocked its potential. “Over the past 10 years, we have worked with Wondo Genet Agricultural Research Center and other partners to bring technology to our farmers,” he says. “Now we are seeing large demonstration fields—barley clusters spanning more than 13 hectares, involving dozens of households. Our farming practices are shifting from traditional to modern.”

OC‑MASSA’s impact is not confined to Bule. In recent seasons, clusters of wheat in Oromia, maize and teff in Amhara, and wheat and barley in Sidama and South Ethiopia have also used the product, with thousands of farmers reporting improved yields on previously acidic land. One report notes that thousands of metric tons of OC‑MASSA have already been distributed to tens of thousands of farmers, as part of efforts to scale up treatment of acidic soils nationwide.

Another important dimension is local production. About 30 percent of OC‑MASSA’s raw materials are now sourced within Ethiopia, giving hope that, as blending plants expand and investments mature, the country could move toward fully domestic production. That would not only improve supply security but also save significant foreign exchange.

OCP Group, the Moroccan phosphate giant behind OCP Ethiopia, has been a strategic partner in this process. Through agreements with the Ethiopian government, including a multi‑billion‑dollar fertilizer complex planned in Dire Dawa, OCP aims to combine Ethiopian potash and gas resources with imported phosphates to make more of the fertilizers the country needs—tailored to its diverse soils.

The Stakes: Food Security and Livelihoods

The stakes could hardly be higher. Agriculture remains the backbone of Ethiopia’s economy, employing around 80 percent of the workforce and contributing more than a third of GDP. Yet an estimated 43 percent of cultivated land is acidic, and in some highland regions the proportion is even higher. Soil acidity directly affects the livelihoods of millions of smallholders and, when family members are counted, may touch the lives of nearly 40 million people.

“When soil pH drops below about 5.5, the soil effectively ‘locks up’ nutrients,” agronomists explain. Even if fertilizers or organic matter are added, plants cannot fully access the nutrients they need, and yield can be cut by half or more. In such a context, tackling acidity is not a luxury—it is a prerequisite for food security.

That is why, in addition to private actors like OCP, development partners such as USAID have also joined efforts to demonstrate and expand the use of locally blended fertilizers for acidic soils, particularly in regions like Sidama. These collaborations aim to boost yields, raise rural incomes, and make Ethiopia’s food system more resilient.

A New Foundation for Hope

Back in Bule, the most powerful evidence of change is not found in policy documents or laboratory reports but in the fields themselves. Stretches of land that once produced sparse, yellowing stands now hold dense, green barley and wheat. Farmers who once spoke of giving up now talk about buying more seed, sending children further in school, and investing in better homes.

“The biggest thing this new technology has given us is confidence,” says Tesfaye. “We are no longer afraid of our own soil.” Worku agrees, adding that OC‑MASSA and the new practices have given him a reason to see farming as a business, not just survival.

The OC‑MASSA story is still in its early chapters. With seven million hectares of acidic land still to be reclaimed, officials like Wondale caution that much work remains. They call for coordinated, “back‑breaking” effort from government, private sector, researchers, and farmers to spread this technology and related practices across the country, making Ethiopia’s highlands lush and green again.

For now, in the hills of Bule, the sight of lush barley swaying in the wind is more than a pretty scene. It is a promise—proof that with the right tools and partnerships, even “dead” soil can be brought back to life, and with it, the hopes of millions of Ethiopian farmers.