The long-standing conflict in Ethiopia’s Konso Zone is primarily driven by water scarcity worsened by climate change, highlighting the complex links between resource depletion, local displacement, and ethnic tensions in the region.

Tirsit Sahledegngel (PhD), a researcher at the Institute of Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University, challenges the conventional view that political or ethnic factors are the main causes of conflict in Konso. She argues that although political and ethnic issues play a role, the underlying root cause is competition over dwindling natural resources like water.

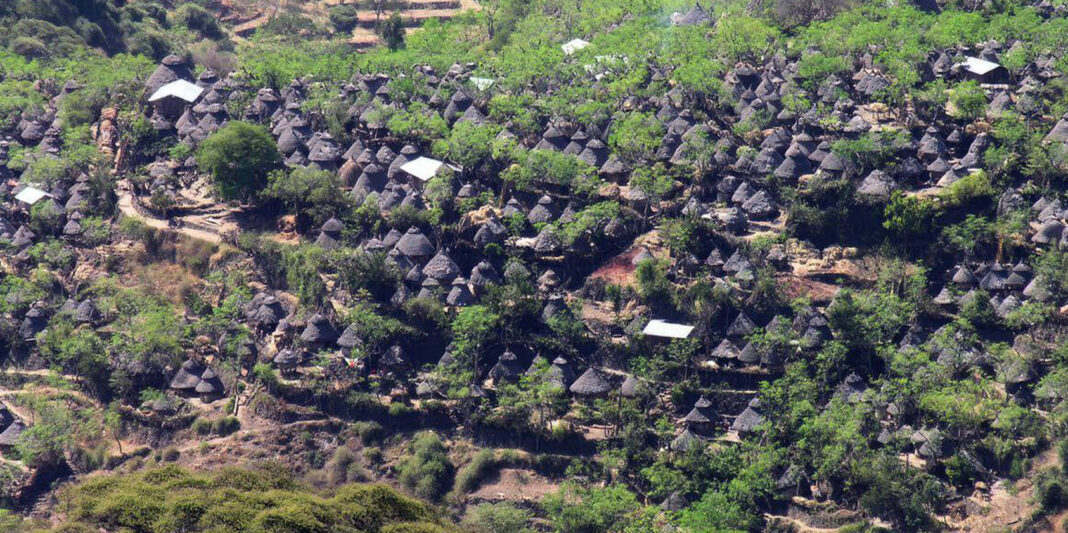

Konso, part of southern Ethiopia, is renowned for its ancient cultural terrace farming system designed to cope with harsh environmental conditions. However, since 2016, the area has suffered severe droughts marked by three consecutive years of inadequate rainfall, worsening the persistent water shortages that fuel conflict, Dr. Tirsit explained.

These insights were shared during the second stakeholder workshop of the Gender, Climate Change and Nutrition (GCAN) initiative, organized by the Forum for Social Studies (FSS). The event focused on the intersections of gender and climate impacts, featuring a study titled “The Nexus Between Climate Change, Gender, and Mobility in Southern Ethiopia,” authored by Tirsit.

The research highlights that in Konso’s rural communities, the burden of collecting water falls largely on women and young girls. Due to water scarcity, these individuals must walk four to five hours daily to remote, often unsafe water sources. This exhausting task has serious consequences, including girls dropping out of school due to the time-consuming water collection.

Moreover, the pressure of domestic labor leads many young girls to seek early marriage as an escape from relentless household duties, Tirsit notes. The study emphasizes that climate change impacts are “disproportionate” because of entrenched gender roles and societal expectations.

Tirsit links this local resource crisis directly to social instability and conflict. Konso’s farming communities depend heavily on rain-fed agriculture, which deteriorates sharply with prolonged droughts. As rains fail, displaced populations increasingly migrate in search of alternative water and fertile land.

Geographically, only two of Konso’s five districts have perennial rivers, exacerbating regional water scarcity. This uneven resource distribution forces communities from dry areas to encroach temporarily or permanently on fertile lands traditionally used by other ethnic groups, often sparking disputes.

Although conflicts are commonly framed as ethnic due to Ethiopia’s federal system linking land to ethnicity, the study shows they primarily represent “resource conflicts” over essential water and land. The conflicts since 2016 have caused extensive displacement and loss of life, representing extreme consequences of ongoing resource depletion, climate change–intensified droughts, and population pressures.

Tirsit describes mobility as an emergent adaptation strategy, with migration becoming crucial when local agriculture can no longer sustain livelihoods.

The study also critiques the use of the term “climate change” as potentially being a donor-driven “buzzword” detached from local realities. From an anthropological perspective, it asks what climate change means for affected communities. Locals interpret it through tangible experiences such as extended dry seasons, unusual flooding, rising temperatures, or disrupted rainy seasons—not abstract scientific concepts.