The Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) has not implemented a robust monitoring system to ensure that coffee products not intended for foreign markets or designated for domestic consumption are traded legally. A recent report by the Office of the Federal Auditor General (OFAG) highlighted significant control gaps concerning “by-products” (unfit for export) and coffee meant for the local market.

In response to these findings, ECX leadership defended their position, stating that the exchange is a marketplace that connects buyers and sellers but does not have the regulatory authority granted under its establishing proclamation.

The controversy centers on coffee exporters who, when selling non‑export grade coffee to licensed wholesalers, allegedly violate the law by not conducting these transactions exclusively through the ECX platform.

The audit reveals that the absence of a clear procedure has allowed products to enter illegal contraband routes. ECX officials, however, argue that their legally defined mandate is limited to linking sellers and buyers, and that they do not possess the power to act as a regulatory or monitoring body.

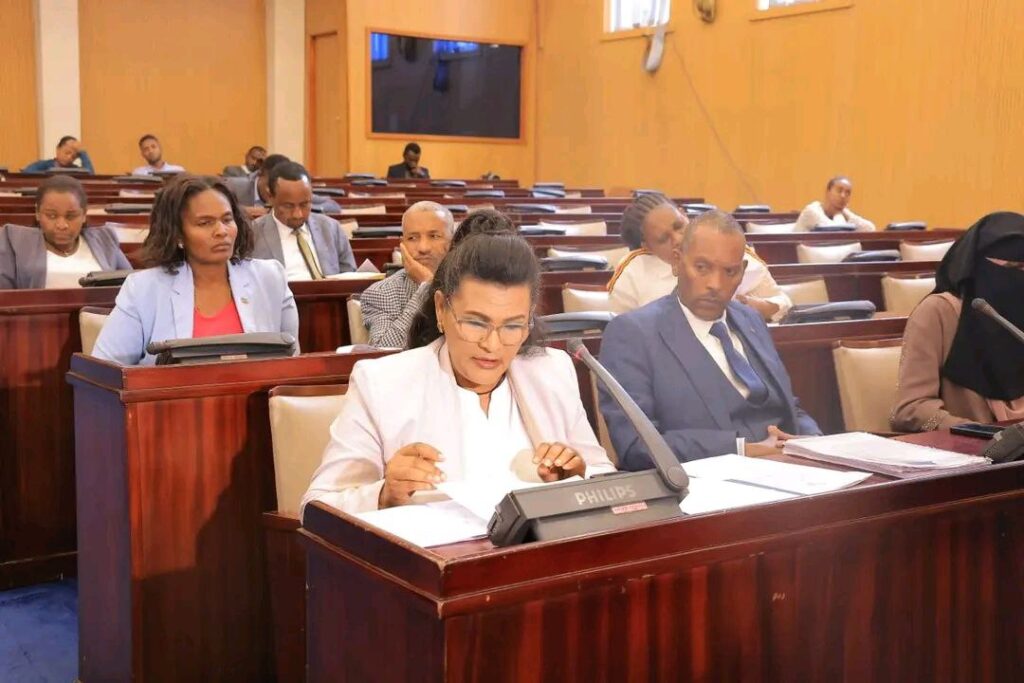

During an official public meeting on December 31, 2025, OFAG was asked to address the findings from an operational audit conducted in the 2023/24 fiscal year, which evaluated ECX’s product intake, inventory, and marketing systems from 2014 to 2016 E.F.Y.

According to Meseret Damte of the Office of the Federal Auditor General, ECX has not established a system to ensure that transactions involving non‑export coffee products are conducted solely through the commodity exchange platform.

The new audit report indicates that while the institution is expected to implement such a system, it has not carried out follow‑up checks to verify compliance during the audit period.

Particularly concerning, as noted in the 2022/23 plan execution report, is the low level of participation by exporters in bringing non‑export products to the commodity market as required.

This situation, the audit warns, increases the risk that such coffee will enter illegal smuggling channels.

The report also notes that there is no effective system in place to coordinate with relevant authorities — including Customs, the Ministry of Trade and Regional Integration, and the police — to help the exchange determine the final destination of these goods.

In its written response to the audit findings, ECX management argued that the proclamation establishing the institution (No. 550/1999) does not grant it regulatory powers.

“The commodity exchange is designed to connect buyers and sellers; it is not authorized by the proclamation to supervise,” the management stated, emphasizing that ECX is fulfilling its responsibility by sending daily market data to the Ministry of Trade and Regional Integration and the Coffee and Tea Authority.

Officials also noted that supervisory bodies are responsible for conducting the necessary monitoring based on the information provided.

They added that the exchange submits quarterly reports to the Coffee and Tea Authority, enabling the authority to use this data for oversight. “We send the data, and the regulators are expected to follow up as needed,” ECX said, insisting that any gaps in enforcement fall under the responsibility of the regulatory institutions.

The government has also established a consignment system that allows exporters to transport purchased products to their own hulling or processing facilities.

The Coffee and Tea Authority, however, has partially shifted responsibility back onto ECX, indicating that while regional authorities manage domestic coffee consumption, data on products sold through the exchange is neither properly organized nor effectively shared with regional trade bureaus, making monitoring difficult.

In addition, some ECX branches — including those in Mizan Teferi and Wolaita Sodo — were found to have facilitated trades outside the price limits set by the Ministry of Trade, indicating a breakdown in the control system. As noted by the Auditor General in a recent discussion, the overall performance of the commodity exchange is a matter of concern, particularly in light of these control gaps.

Beyond regulatory shortcomings, the audit report highlighted the poor condition of several ECX warehouses. The Bonga warehouse suffers from cracked floors and lacks fencing, while the Humera warehouse is vulnerable to flooding and has a leaking roof.

Warehouses in Adama, Erbe‑Hajira, and Bure were also deemed inadequate, lacking sufficient truck parking and sampling space. These facilities, which fall short of modern infrastructure standards, hinder product quality assurance and timely service, pushing some suppliers toward informal and illegal trading channels.

The report further criticized ECX’s IT system, citing a lack of transparency and accountability that has obscured processes and weakened confidence in the platform.

Moreover, instead of formally updating the exchange’s regulations, there is a pattern of changing guidelines through ad hoc orders from the board or the supervising ministry. This “order‑driven” approach has created an opaque and unpredictable market environment for private sector participants.

Although the commodity exchange was established partly to benefit small producers, the audit revealed that this objective has not been achieved in practice. Over the past three years, no specific initiatives have been planned or implemented to support smallholder farmers.

Most farmers struggle to access timely market information. Because the exchange disseminates market data primarily via Telegram, farmers without access to the app are left in the dark and are more easily exploited by middlemen.

According to the report, between 2022 and 2024, transaction volumes on the ECX fell by between 14% and 51%, while the value of traded commodities declined by between 13% and 30%.

Contributing factors include members shifting to alternative marketing channels, IT system failures and congestion, poor warehouse conditions, delays in board meetings, and slow resolution of operational problems.

Separately, the House of Peoples’ Representatives raised concerns over ECX’s failure to conduct annual financial audits by external auditors since 2010 E.C.

In revenue terms, 22.7% (approximately 467 million birr) of the more than 2 billion birr planned to be collected over three years remains uncollected. The audit concludes that this financial shortfall could hinder the implementation of much‑needed reforms within the institution.